Case Study Date: 20191

League City is a bedroom suburb of Houston with a population of 83,500, which is still rapidly growing. It has faced four flood events that were designated by Presidential Disaster Declarations since 2000.

Plans Evaluated

- League City Comprehensive Plan 2013

- City of League City Local Mitigation Plan, 2010

- 5-Year Strategic Plan for League City, Texas

- City of League City, Texas Parks & Open Space Master Plan

Summary of Findings

The overall network of plans in League City is highly integrated and supports the reduction of vulnerability to flooding. All the plans share a common policy focus to protect people and structures from flooding by facilitating development and/or environmental practices that support flood mitigation. However, the plans fail to target the districts with greater physical vulnerability to flooding. When concerning exclusively about equity policies, League City’s network of plans is generally integrated in vulnerability reduction and succeeds in targeting the more socially vulnerable districts.

League City, TX

League City, TX is a bedroom suburb of Houston located in a low-lying coastal region facing significant flooding and hurricane hazards. The city has experienced four major flood events since 2000 that were designated by Presidential Disaster Declarations and thus eligible for federal recovery funds. Additionally, the city is rapidly growing with a population that is projected to rise from 83,500 in 2010 to 228,000 in 2040 (League City, 2013, as cited in Malecha et al., 2019). The current land use patterns there are dominated by conventional developments characterized by low-to-moderate density suburban residential neighborhoods, commercial strip corridors, and retail centers. About 4,730 acres (15% of the city’s total land area) is in the 100-year floodplain mostly due to the Clear Creek riparian area that runs east to west through League City. Of the floodplain lands, only 496 acres are designated as permanent open space (public parkland and conservation areas), while the remaining 4,234 acres of floodplain lands are privately owned. The city can potentially be subject to further developments in the floodplain since about 57% of the privately-owned floodplain land is undeveloped. Past floodplain development has fragmented aquatic systems and filled in wetlands along major coastal creeks and lake shorelines, which offer critical flood mitigation functions.

Findings of the Overall Network of Plans

League City’s network of plans is highly integrated and supports a common policy framework aimed at hazard vulnerability reduction. The introduction of the comprehensive plan reflects the city’s strong commitment to plan integration, as indicated by its explicit goal to take into account other plans and tie together the solutions from other plans.

All plans include similar hazard goals to protect people and structures through sound development and/or environmental practices that support flood mitigation. The comprehensive plan, mitigation plan, and parks plan contain the city’s future land use map to guide future new development and redevelopment.

However, the network of plan in League City fails to target the districts with greater degree of physical vulnerability. It is revealed by the negative Pearson’s r correlation (-0.63) between the summed policy scores each district of League City receives and the degree of physical vulnerability there. In fact, the negative correlation is the greatest in League City compared to the other five cities the same study investigated (i.e., Washington, NC; Asbury Park, NJ; Fort Lauderdale, FL; Tampa, FL; Boston, MA). The negative correlation suggests that League City’s plan network prioritizes steering development away from, or limiting development in, the districts with a lower degree of physical vulnerability.

There has also been a PIRS study specifically focusing on the equity policies in League City, referring to the policies aiming at rectifying issues of distributional inequity. This portion of plan network receives a moderately positive overall mean score, suggesting that its equity policies, overall, are integrated and support the reduction of vulnerability to flooding. Additionally, it targets the more socially vulnerable district, making it the only city doing so among the five cities being investigated by the same study. It is revealed by the fact that the equity-policy portion of the plan network has positive Pearson’s r correlations for both the hundred-year floodplain (+0.32) and the projected sea level rise area (+0.34). However, the city’s approach is narrowly focused. The positive correlations arise because the main focus of the housing plan is to upgrade the existing infrastructure (stormwater drainage, water, sewer, and streets) in underserved neighborhoods with high levels of social vulnerability to be more flood resilient. However, the housing plan is the only plan among the four plans adopted by League City to include equity policies.

Findings from Specific Case-Study – Challenger Seven Memorial Park District

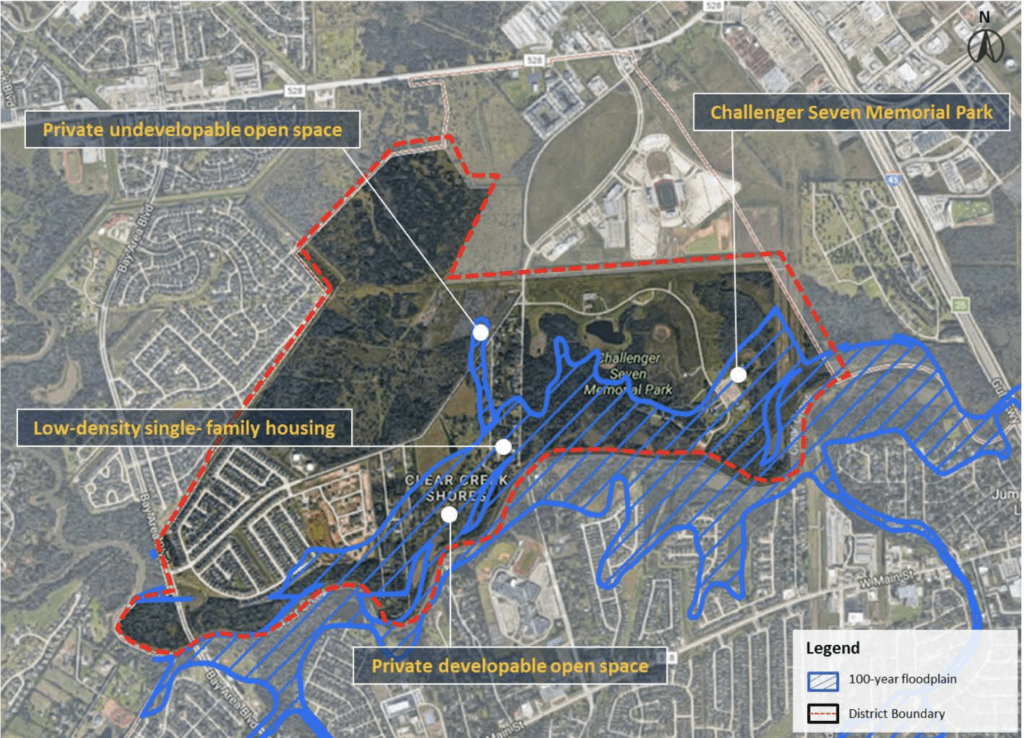

Challenger Seven Memorial Park District (District 7; see Figure 1) showcases an example where a network of plans has innovative policies to reduce vulnerabilities but fails to target the high vulnerability areas. Its plan integration score is the fifth highest (+37), but its physical vulnerability is the third lowest among the city’s 21 districts. About 22% (197 acres) of the district is located in the 100-year floodplain. Of the current floodplain land uses,

- 55% (110 acres) is designated as park,

- 31% (60 acres) as private developable open space, and

- 14% (27 acres) as low-density single-family housing.

Among the four plans, only the comprehensive plan includes policies that support more development in the floodplain in this district. These include zoning policies that allow “granny flats” in existing single-family homes and that designate privately owned open spaces for low-density development. However, the plans place more attention on avoidance of future development in the floodplain, especially in the Clear Creek riparian area that runs along the southern boundary of the district (see Figure 1).

Note. Adapted from Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard Guidebook: Spatially Evaluating Networks of Plans to Reduce Hazard Vulnerability – Version 2.0 (p.82), by M. L. Malecha, J. H. Masterson, S. Yu, P. R. Berke, 2019, Institute for Sustainable Communities, College of Architecture, Texas A&M University planintegration.com/pirs-guidebook

There are several prominent themes of policies working together to reduce new floodplain development in the district.

Policy theme 1:

Land use regulations aimed at reducing vulnerability in undeveloped floodplains

- The comprehensive plan proposes new floodplain development with buffer regulations to preserve floodplain riparian lands.

- The comprehensive plan proposes subdivision regulations that require clustering and open space dedication standards for setting aside natural areas that include floodplains.

- The implementation elements of the hazard mitigation plan and parks plan explicitly indicate that the city revise ordinances to be consistent with the proposed changes in the comprehensive plan.

Policy theme 2:

Public spending for land acquisition in proposed conservation areas in undeveloped floodplains

- The comprehensive plan, parks plan, and hazard mitigation plan all specify the land acquisition funds to be used to target riparian areas and wetlands that serve to mitigate flood impacts, provide recreation and water conservation benefits, and create trails that link open spaces.

Policy theme 3:

Public facility investments aimed at reducing impacts of flooding

- The comprehensive plan and parks plan support investment in stormwater management facilities (e.g., rain gardens and swales) in parks to provide flood mitigation and other environmental benefits to surrounding neighborhoods.

- The parks plan and hazard mitigation plan propose a string of flood detention lakes connected by trails for a regional drainage corridor.

- The mitigation plan prohibits construction of government buildings and special needs facilities (medical facilities, nursing homes) in floodplains.

Policy theme 4:

Development limits are tied to evacuation times for new developments

- The hazard mitigation plan and comprehensive plan support setting density limit standards due to the impacts of new development on evacuation times along emergency routes.

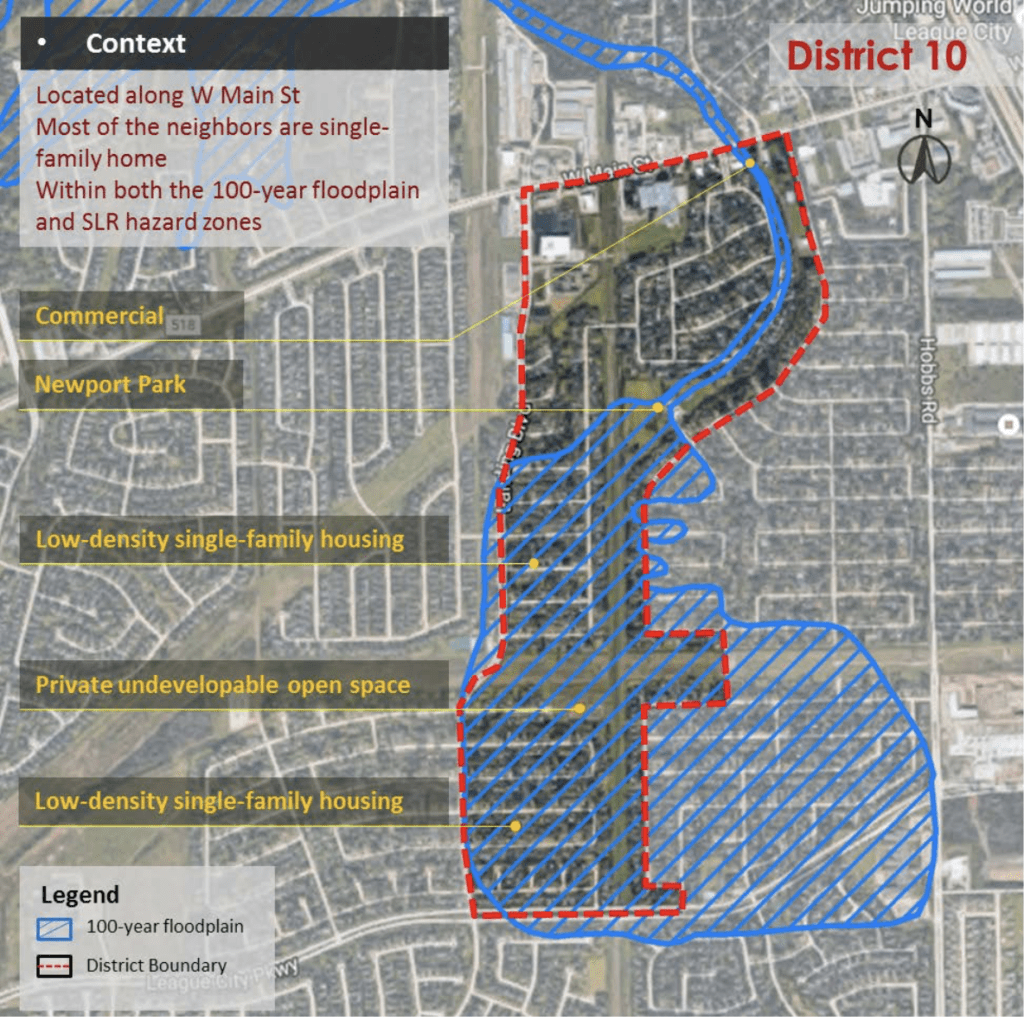

Findings from Specific Case-Study – West Main Street District:

The West Main Street District (District 10; see Figure 2) exemplifies how the network of plans gives far less attention to reducing vulnerability in districts that are more physically vulnerable. The district has the fourth lowest policy score (+12) but the sixth highest physical vulnerability among the 21 districts in the city. About 46% (100 acres) of the district is located in the 100-year floodplain, with limited opportunity for new development. Roughly,

- 71% (71 acres) of the floodplain land is used as low-density single-family housing,

- 5% (5 acres) in commercial use,

- 2% (2 acres) as park land.

- The remaining floodplain land use includes privately owned open space that is undevelopable (22%, 22 acres).

Note. Adapted from Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard Guidebook: Spatially Evaluating Networks of Plans to Reduce Hazard Vulnerability – Version 2.0 (p.84), by M. L. Malecha, J. H. Masterson, S. Yu, P. R. Berke, 2019, Institute for Sustainable Communities, College of Architecture, Texas A&M University planintegration.com/pirs-guidebook

Policies in the comprehensive plan support increased development in the 100-year floodplain in this district, including zoning policies that support infill development by allowing a “granny flat” into any existing single-family home. Also included are design guidelines that support infill on large lots currently occupied by a residential unit that can be subdivided. West Main Street District does not include any high priority conservation district. As a result, many of the conservation protection policies that are relevant to Challenger Seven Memorial Park District (District 7) are not applicable in District 10. Despite this, a few policies work to reduce the flood vulnerability of existing developments:

- Public facility investment policies aimed at reducing impacts from flooding appear in comprehensive plan, hazard mitigation plan, and parks plan. Examples include best practices for stormwater mitigation (e.g., pervious pavement for parking lots, detention ponds, rain gardens, and vegetative swales), and purchase of drainage easements in the floodplain.

- Affordable housing is applied with a stormwater drainage infrastructure policy aimed at an existing underserved, low-income neighborhood in floodplain areas. Nonetheless, this policy is not coordinated with other plans.

- The hazard mitigation plan includes a land acquisition program for repetitive flood loss properties in existing neighborhoods, but the targeting of properties is not coordinated with the future land use policies in the comprehensive plan or other local plans.

- The data here refers to the year in which a publication containing PIRS-related information about the case-study site was published.

References

Berke, P. R., Malecha, M. L., Yu, S., Lee, J., & Masterson, J. H. (2019a). Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard: Evaluating Networks of Plans in Six US Coastal Cities. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 62(5), 901-920. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2018.1453354

Berke, P. R., Yu, S., Malecha, M. L., & Cooper, J. (2019b). Plans that Disrupt Development: Equity Policies and Social Vulnerability in Six Coastal Cities. Journal of Planning Education and Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X19861144

Malecha, M. L., Masterson, J. H., Yu, S., & Berke, P. R. (2019). Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard Guidebook: Spatially Evaluating Networks of Plans to Reduce Hazard Vulnerability – Version 2.0. Institute for Sustainable Communities, College of Architecture, Texas A&M University. planintegration.com/pirs-guidebook

Yu, S., Malecha, M. L., & Berke, P. R. (2021). Examining Factors Influencing Plan Integration for Community Resilience in Six US Coastal Cities Using Hierarchical Linear Modeling. Landscape and Urban Planning, 215, 104224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104224