Case Study Date: 2019

Fort Lauderdale is the principal city of the Miami metropolitan area, home to a population of 5,564,635. Most of the city has already been built up. It is one of the urban area most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change in the world.

Summary of Findings

Fort Lauderdale’s network of plans, overall, reduces the city’s vulnerability to flooding. However, the network pays much attention to developing and redeveloping the areas of regional significance. Concerning equity policies specifically, the network still generally supports vulnerability reduction in the hundred-year floodplain. However, it heightens vulnerability in the sea level rise area, another hazard zone in the city. Meanwhile, the equity-policy portion of the network fails to target the more socially vulnerable districts.

Plans Evaluated

- 2008 Fort Lauderdale Comprehensive Plan

- 2012 Enhanced Local Mitigation Strategy for Broward County

- 2014 Broward County Comprehensive Plan

- The City of Fort Lauderdale 2010 – 2015 Consolidated Plan

- 2007 Downtown Master Plan

- 2008 Downtown New River Master Plan

- 2007 Davie Boulevard Corridor Master Plan

- 2004 South Andrews Avenue Master Plan

Fort Lauderdale, FL

Fort Lauderdale is the largest city in Broward County, Florida. Located along the state’s southeastern coast and nicknamed the “Venice of America” due to its many canals, the city includes 337 miles of coastline. It is the principal city of the Miami metropolitan area, which is home to 5,564,635 people (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010, as cited in Malecha et al., 2019) and is considered one of the world’s most vulnerable urban areas with respect to climate change and hazard events. Fort Lauderdale faces severe flooding, thunderstorm, tornado, and hurricane hazards (Broward County, 2012, as cited in Malecha et al., 2019). The city is almost entirely built out, with only four percent of land remains vacant (City of Fort Lauderdale, 2008, as cited in Malecha et al., 2019). As a high-amenity location, however, the city has much potential for redevelopment – including in the 100-year floodplain, which encompasses approximately 44% of the city. Land use in Fort Lauderdale is a mix of:

- 55% residential (41%),

- utility (34%),

- commercial (12%),

- industrial (6%), and

- institutional (3%) uses.

Findings of the Overall Network of Plans:

Fort Lauderdale’s network of plans is well-integrated and generally reduces vulnerability to hazards. The Coastal Management Element of the city’s comprehensive plan essentially satisfies the requirements of Chapter 163 of Florida Statutes, which states that “local coastal governments plan for [and] restrict development where development would damage or destroy coastal resources and protect human life and limit public expenditures in areas that are subject to destruction by natural disaster” (Fort Lauderdale, 2008, p.4-1, as cited in Malecha et al., 2019).

The county’s hazard mitigation plan places high priority on mitigating floodplain development in highly vulnerable areas. Throughout the city’s network of plans, however, much attention has been paid to developing and redeveloping areas of regional significance, known as Regional Activity Centers (RACs).

For the PIRS analysis concerning exclusively about equity policies, Fort Lauderdale’s plan network has a mixed result: it supports vulnerability reduction in hundred-year floodplain but slightly worsens the vulnerability in the sea level rise area. Meanwhile, the equity-policy portion of the plan network fails to target the more socially vulnerable districts. It is revealed by the fact that the Pearson’s r correlation between a district’s social vulnerability and its summed policy scores is -0.24 for hundred-year floodplain and -0.26 for the projected sea level rise areas.

Findings from Specific Case-Study – Lauderdale Beach/Dolphin Isles:

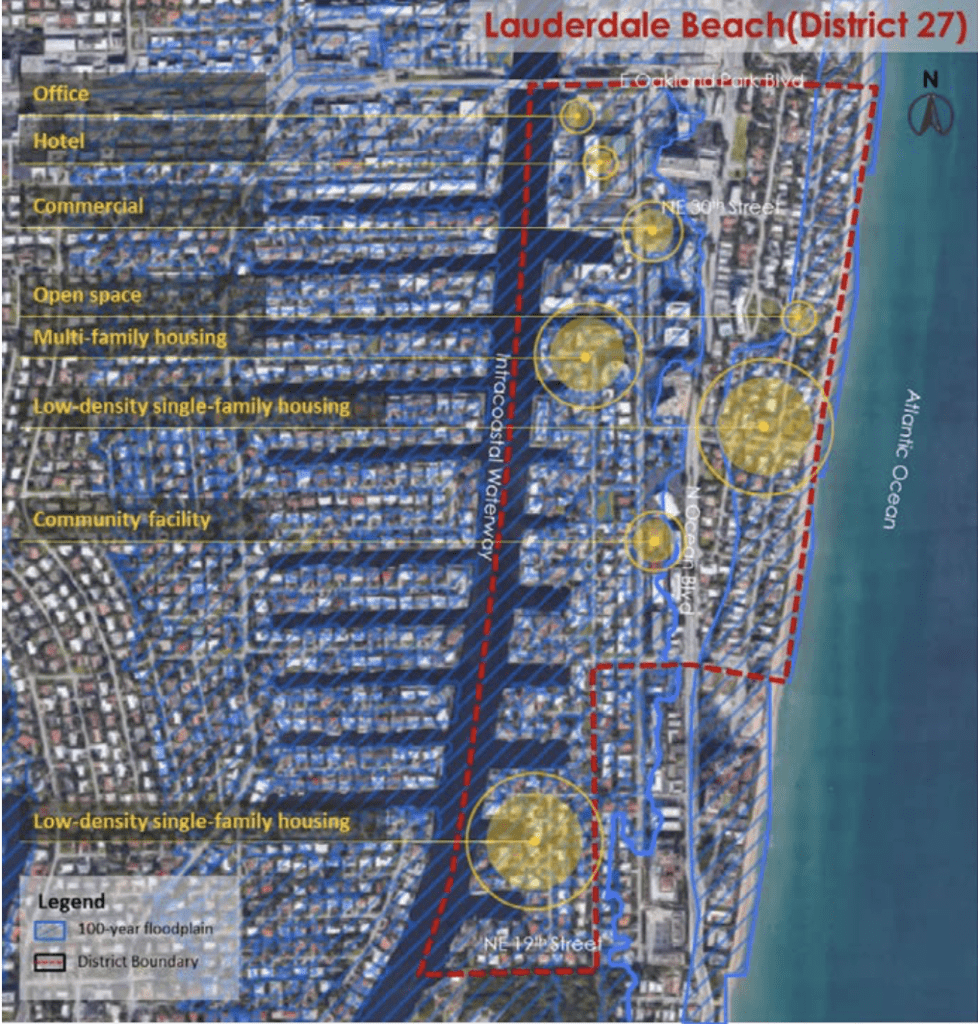

Lauderdale Beach/Dolphin Isles (District 27; see Figure 1) showcases an example in which a planning district is almost entirely developed and highly vulnerable, yet the city still manages to fully integrate plans and pursue innovative policies to reduce vulnerabilities.

Lauderdale Beach/Dolphin Isles is a predominately residential neighborhood located between the Intracoastal Waterway and the Atlantic Ocean in eastern Fort Lauderdale. It is entirely within the state-designated Coastal High Hazard Area (CHHA; City of Fort Lauderdale, 2008, as cited in Malecha et al., 2019), an overlay zone. It is one of the top ten districts in Fort Lauderdale in terms of physical vulnerability and is the third highest district in terms of policy score (+45). As Figure 1 shows, about 61.7 % (99 acres) of the district is located in the 100-year floodplain. Within this hazard zone, land uses are:

- low-density single-family housing (58%, 58 acres),

- multi-family housing (25%, 25 acres),

- community facility (5.4%, 5 acres),

- hotel (0.3%, 0.3 acres),

- commercial (4.9%, 5 acres),

- office (1%, 1 acre), and

- open space (0.3%, 0.3 acres).

53 polices across three plans (city comprehensive plan; county local mitigation strategy; county comprehensive plan) affect Lauderdale Beach/Dolphin Isles. Among these 53 policies, only four are likely to increase vulnerability by promoting redevelopment and reuse, which are all in the city comprehensive plan. Three of them are linked to development regulations and one is tied to post-disaster reconstruction decisions.

Note. Adapted from Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard Guidebook: Spatially Evaluating Networks of Plans to Reduce Hazard Vulnerability – Version 2.0 (p.87), by M. L. Malecha, J. H. Masterson, S. Yu, P. R. Berke, 2019, Institute for Sustainable Communities, College of Architecture, Texas A&M University planintegration.com/pirs-guidebook

All three plans applicable to this district focus more on vulnerability reduction. Several prominent themes of policies work together to reduce existing vulnerability and to prevent vulnerability that can potentially arise from future developments or redevelopments in Lauderdale Beach/Dolphin Isles.

Policy theme 1:

Development regulations aimed at protecting coastal and hazard-prone areas

- Policies throughout the city and county comprehensive plans encourage protection and conservation of existing natural beaches, berm areas, wetlands, and other types of open space in coastal and hazard-prone areas.

- Policies that regulate inappropriate development and limit land use densities and intensities within the CHHA overlay zone in sensitive areas such as floodplains (short-term focus on the 100-year floodplain and long-term focus on the 500-year floodplain).

- Enforcement and monitoring are also encouraged to comply with the regulations of the Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s Coastal Construction Control Line (CCCL), a statewide program to protect the state’s beaches and dunes.

- Several polices suggest an inventory of hazard-prone properties throughout the city, which may result in the implementation of development regulations to reduce future property damages and losses, such as setback provisions and other site controls.

Policy theme 2:

Land acquisition and land use guidelines aimed at reducing vulnerability for new development and redevelopment in coastal and hazard prone areas

- Fort Lauderdale’s comprehensive plan contains policies suggesting that undeveloped lands in the CHHA overlay zone should be considered for acquisition for restoring them into their natural state or turning them into recreation or open space.

- All new construction along the beachfront should be consistent with design guidelines and criteria established during the designation of the CCCL.

- The impacts of development or redevelopment are to be limited with respect to wetlands,

water quality and quantity, wildlife habitat, living marine resources, and beach dune system. Similarly, drainage and stormwater management in new developments should follow designated standards to mitigate future impacts.

Policy theme 3:

Directing capital funding related to coastal and hazard-prone areas

- Policies in Broward County’s comprehensive plan and the hazard mitigation plan direct public expenditures to improve public infrastructure in the CHHA overlay zone, such as existing wellfields, surface or subsurface storage facilities, control structures, water and wastewater treatment plants, and transmission infrastructure.

- Several policies in the county’s comprehensive plan propose the capital improvement funds to focus on projects which restore the dune system and enhance natural resources, such as via beach nourishment.

- Policies in the hazard mitigation plan require that hazard mitigation considerations to be linked to the capital improvement funding process.

Like much of Fort Lauderdale, the Lauderdale Beach/Dolphin Isles neighborhood is almost fully built up while much of it is within the 100-year floodplain. Thus, options to reduce physical vulnerability are limited. Rather than directing new development to less hazardous areas, which can be a good option for cities not yet much built-up and/or having substantial lands outside the hazard zone, the Lauderdale Beach/Dolphin Isles district (and Fort Lauderdale as a whole) must build resilience and plan integration through measures that can be applied in situ. The policy themes described above may be complemented through several additions:

- In addition to requiring new development in the CHHA overlay zone to meet certain criteria, Fort Lauderdale’s network of plans could focus on elevation requirements for existing structures. They could direct grants and funding to support further preventative elevation of single-family and multi-family structures which already exceeds the current flood safety standards.

- To enhance the land acquisition strategy in Fort Lauderdale’s comprehensive plan, density transfer and transfer-of-development programs covering hazard-prone coastal neighborhoods like Lauderdale Beach/Dolphin Isles could be encouraged.

- In addition to protecting the coastal ecology through conservation, overlay regulations, and beach nourishment, vulnerability could be reduced by directing capital funds to more holistic vegetation-based approaches, such as encouraging reforestation and vegetated dunes on the seaward side and mangrove areas in the canals.

Findings from Specific Case-Study – Sistrunk Neighborhood:

The Sistrunk neighborhood in Fort Lauderdale illustrates the kind of critical equity policy and risk issues associated with the inverse relationship between equity policy and social vulnerability. Fort Lauderdale is a leader in hazard mitigation and adaptation to climate change. The city’s recent vision statement, for example, places considerable attention to envisioning a resilient city confronted by coastal hazards and climate change. Yet, the equity policies in the city’s plans do not support reducing risk in the highly socially vulnerable Sistrunk neighborhood.

Findings in Sistrunk represent the pattern of inconsistency between equity policy and social vulnerability not uncommon among the cities investigated by the same study (i.e., League City, TX; Washington, NC; Asbury Park, NJ; Tampa, FL; Boston, MA). Sistrunk is a historically poor, black neighborhood established during the Jim Crow era of the early 1900s. It has the lowest negative policy score among all districts but the highest level of social vulnerability. This inverse relationship arises because of a prominent theme in the housing plan, which uses the enterprise zone program to steer the redevelopments that are entirely exposed to the hundred-year floodplain and projected sea level rise. The core goals of the program are to stimulate business investment, jobs, and affordable housing in blighted areas. It also aims to support infrastructure investment for more on-street parking, wider sidewalks, streetlights, landscape enhancements, and new bus shelters. Examples of enterprise zone policies include property tax credits, low interest loans, and tax increment financing. Except the mitigation plan, equity policies in other plans with jurisdiction over the Sistrunk neighborhood do not address risk reduction. Rather, they give significant attention to stimulating more development in a hazardous location dominated by a socially vulnerable population.

The inverse relationship between social vulnerability and equity policies raises a hazard-related social justice problem. It is that efforts to stimulate redevelopment in socially vulnerable districts may bring unwelcome consequences in the form of a paradox: development could exacerbate risk in hazard areas, which in turn could severely disrupt progress in development due to the rising likelihood of loss. It in turn locks the poor neighborhoods into existing inequity as the hazard threat rises.

The solution to this paradox is far from obvious. How should networks of plans be adapted to both improve social and economic conditions in socially vulnerable neighborhoods, while simultaneously reduce risk? How should policies and implementation actions in plans be revised to address the risks, values, and needs of socially vulnerable populations?

References

Berke, P. R., Malecha, M. L., Yu, S., Lee, J., & Masterson, J. H. (2019a). Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard: Evaluating Networks of Plans in Six US Coastal Cities. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 62(5), 901-920. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2018.1453354

Berke, P. R., Yu, S., Malecha, M. L., & Cooper, J. (2019b). Plans that Disrupt Development: Equity Policies and Social Vulnerability in Six Coastal Cities. Journal of Planning Education and Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X19861144

Malecha, M. L., Masterson, J. H., Yu, S., & Berke, P. R. (2019). Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard Guidebook: Spatially Evaluating Networks of Plans to Reduce Hazard Vulnerability – Version 2.0. Institute for Sustainable Communities, College of Architecture, Texas A&M University. planintegration.com/pirs-guidebook