Case Study Date: 2021 (during the time of Hurricane Harvey)

The case-study site is a relatively affluent part of Houston. It also has a comparatively high percentage of White population. Economically, it is the home of the headquarters and regional offices of numerous energy companies, making it the second largest employment center of the region. Nonetheless, due to increasing urbanization, the area has become more vulnerable to flooding these years.

Brief Summary of Findings

The plan network applying to the case-study site, overall, reduced physical vulnerability to flooding in every of the planning districts during the time of Hurricane Harvey. However, there were important variations and conflicts across plans and between different parts of the case-study site. Policies worsening vulnerability were particularly impactful in places outside the 100-year floodplain.

Plans Evaluated

- Our Great Region 2040 (including the ‘Strategy Playbook’)

- Houston Stronger

- Gulf-Houston Regional Conservation Plan

- 2040 Houston-Galveston Regional Transportation Plan (RTP) + 2017–2020 Transportation Improvement Plan (TIP)

- Harris County Flood Control District 2017 Federal Briefing

- City of Houston Hazard Mitigation Plan Update

- Plan Houston

- Houston Parks & Recreation Department Master Plan

- The Energy Corridor District Unified Transportation Plan, 2016–2020

- The Energy Corridor District 2015 Master Plan

- Energy Corridor Livable Centers Plan

- Energy Corridor Bicycle Master Plan

- Memorial City Management District 2014–2024 Service and Improvement Plan and Assessment Plan

- Westchase District Long Range Plan

- West Houston Plan 2050: Envisioning Greater West Houston at Mid-Century

- West Houston Trails Master Plan

- West Houston Mobility Plan

- 2009 Master Plan, Addicks and Barker Reservoirs, Buffalo Bayou and Tributaries, Fort Bend and Harris Counties, Texas

Western Houston, TX

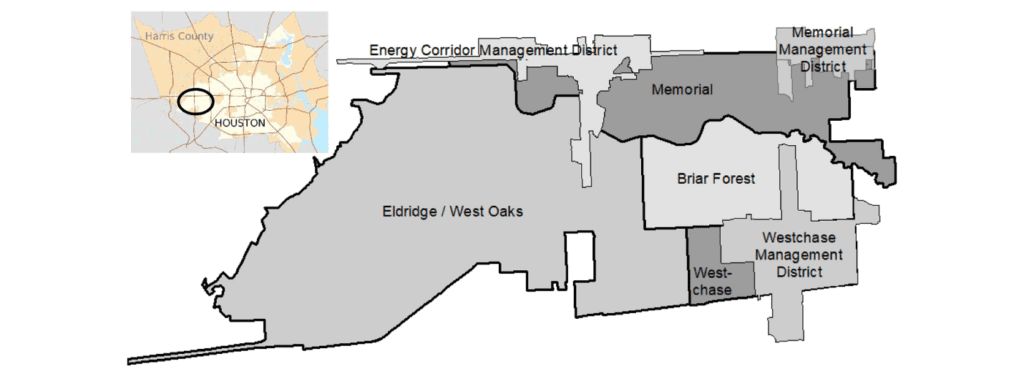

The PIRS evaluation focused on a cluster of four super neighborhoods – Briar Forest, Eldridge/West Oaks, Memorial, and Westchase – and three municipal management districts – Energy Corridor, Memorial, and Westchase – in western Houston (see Figure 1). The former denotes an administrative and planning division unique to Houston (Neuman, 2004), whereas the latter comprises special districts created by the Texas Legislature to coordinate and promote development and public welfare (State of Texas Local Government Code, 2005, as cited in Malecha et al., 2021). The 122.5 km2 study area is home to approximately 200,000 residents (City of Houston, 2019, as cited in Malecha et al., 2021). These neighborhoods have higher than average median household incomes and percentages of white residents compared to the city as a whole (City of Houston, 2019, as cited in Malecha et al., 2021). The study area also is home to headquarters or regional offices of numerous energy companies, including Shell and BP, making it the second largest employment center in the region (Energy Corridor District, 2015, as cited in Malecha et al., 2021). It should be noted that the PIRS evaluation focused on the situation of these areas during the time of Hurricane Harvey.

Note. Adapted from Planning to Exacerbate Flooding: Evaluating a Houston, Texas, Network of Plans in Place during Hurricane Harvey Using a Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard, by M. L. Malecha, S. C. Woodruff, P. R. Berke, Natural Hazards Review, 22(4), p. 04021030-3 (https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000470). Copyright 2021 by American Society of Civil Engineers.

Despite its relative affluence, this part of the city suffered extensive damage during Hurricane Harvey. Located immediately downstream from the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs, the area was inundated not only by the unprecedented rainfall accumulation, but also as a result of controlled releases from the reservoirs to prevent catastrophic dam failure (Blake and Zelinsky, 2018). Releases began on August 28 and continued until September 20; only then did floodwaters begin to recede from the area (Harris County Flood Control District [HCFCD], 2018a).

Following the catastrophic flooding in the 1930s, the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs were built to protect downtown Houston from flooding (United States Army Corps of Engineers [USACE], 2009). The reservoirs were designed to collect excessive rainfall and release water into Buffalo Bayou at a controlled rate. Although releases from the reservoir devastated downstream neighborhoods during Harvey, the dams successfully protected downtown Houston, the Houston Ship Channel, and Port Houston (HCFCD, 2018b, as cited in Malecha et al., 2021).

Flooding below the dams in this part of Houston has become a greater threat as urban development has intensified (USACE, 2009). Continued development downstream has placed more people and property in risky locations, whereas development upland, near the western edges of the rarely filled reservoirs (USACE, 2009), has resulted in additional pressure and less room for the reservoir to function. Thus, it is critical that the plans guiding this development are coordinated and that hazard awareness is integrated throughout the entire network of plans.

Unlike many parts of this notoriously planning-averse city [although that perhaps is an unfair characterization (cf. Neuman, 2004)], this prominent section of Houston has received a great deal of policy attention from plans at multiple administrative scales. Development in the case-study site was guided during the time of Harvey by 18 separate plans, developed by regional, city, and neighborhood entities (and combinations thereof). Municipal management districts, which are empowered to promote economic development and public welfare, also had developed numerous plans to guide future development. This enables a robust exploration of the relationships between plans, including at different administrative scales (Woodruff, 2018; Yu et al., 2020), as well as of the potential effects of policies that applied to one area but affected another – e.g., policies that encouraged new development in an upland location increasing flood risk in downstream areas (Brody et al., 2011).

Findings of the Overall Network of Plans:

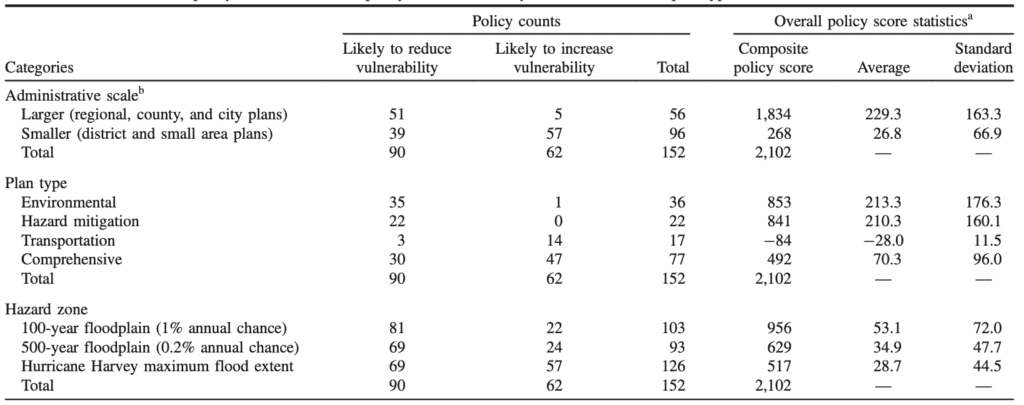

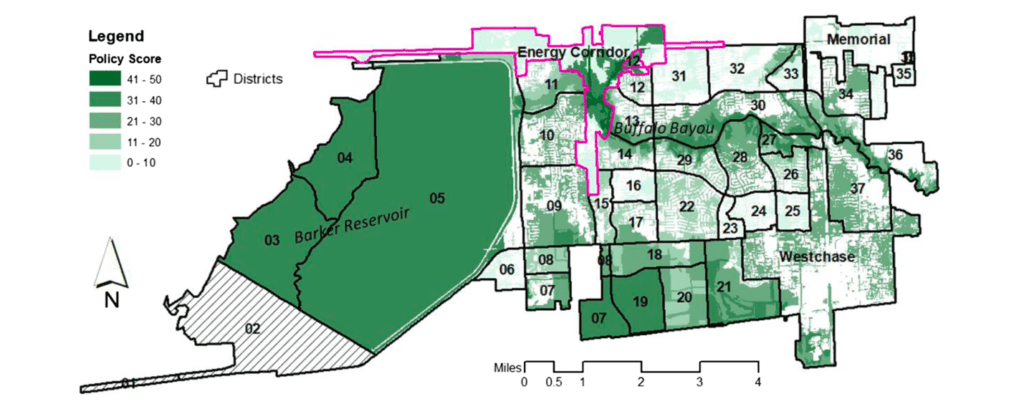

Results from the PIRS evaluation indicated that the network of 18 plans guiding development and land use in western Houston when Hurricane Harvey struck generally supported reduction of flood vulnerability. Of the 152 land-use policies across the network of plans that were likely to influence physical vulnerability to flooding, many more were focused on reducing it (90) than were likely to increase it (62) (see Table 1). Across the entire case-study site, not a single district-hazard zone received a negative overall policy score (see Figure 2), which would have indicated that the mix of policies affecting that part of the city were, as a whole, guiding it in a more vulnerable direction. This positive overall picture, however, belied hidden patterns within the network of plans and across hazard zones, including apparent conflicts between policies in some areas, which are discussed in greater detail subsequently and illustrated in an in-depth case study of the Energy Corridor District.

b Administrative scale groupings are based on geographic scope (larger than study area versus smaller than study area).

Table 1: Scorecard results: policy counts and overall policy score statistics by administrative scale, plan type, and hazard zone.

Note. Adapted from Planning to Exacerbate Flooding: Evaluating a Houston, Texas, Network of Plans in Place during Hurricane Harvey Using a Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard, by M. L. Malecha, S. C. Woodruff, P. R. Berke, Natural Hazards Review, 22(4), p. 04021030-6 (https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000470). Copyright 2021 by American Society of Civil Engineers.

Note. Adapted from Planning to Exacerbate Flooding: Evaluating a Houston, Texas, Network of Plans in Place during Hurricane Harvey Using a Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard, by M. L. Malecha, S. C. Woodruff, P. R. Berke, Natural Hazards Review, 22(4), p. 04021030-6 (https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000470). Copyright 2021 by American Society of Civil Engineers.

Findings by Administrative Scale

Stark differences existed between larger-scale and smaller-scale plans (see Table 1). Policies in the eight regional-, county-, and city-scale plans were often more positive and wider ranging (i.e., affecting more district-hazard zones) than those found in the ten neighborhood and small area plans, though the latter included more total policies likely to affect physical vulnerability. Of the policies in the larger-scale plans, 91% (51 of 56) supported reduction of flood vulnerability, whereas only 41% (39 of 96) of the neighborhood and small area plan policies guided the community in a less vulnerable direction. However, the broader geographic scope of these vulnerability-reducing policies – such as those protecting natural riparian areas along bayous – made the overall policy score averages of the smaller-scale plans positive. The smaller-scale plans had an average of 26.8 per plan, whereas the larger-scale plans averaged 229.3.

These patterns among the smaller-scale plans were influenced heavily by the prominence of development and transportation policies the plans contained, whereas the city, county, and regional plans were focused mainly on environmental, safety, and connectivity issues. Being closer to the action, neighborhood and small area plans were also frequently required to balance many competing needs – including the classic development-versus-preservation challenge – whereas larger-scale plans could generally avoid such issues. Houston’s city-scale plans were less affected by these competing drivers than might have been expected. This might be an artifact of the city’s recent reembracing of citywide planning, and the preliminary, largely visionary nature of the Plan Houston document.

The differences between plan scale suggested key jurisdictional relationships in the Houston region, including a preference among city and county administrations to leave most land-use and development issues to be decided by local actors, thus focusing their planning and resources on regional issues such as parklands, waterways, and transportation routes. Without sufficient cross-agency communication, however, this approach could make policies at the larger-scales conflict with those in the smaller-scale plans. For example, policies in large-scale parks or hazard mitigation plans aimed at preserving natural areas sometimes clashed with those in local master plans aimed at intensifying development in some of the same areas.

A well-defined process that mandates a degree of inter-administrative consistency and promotes consensus would reduce many such conflicts. Successful examples of this includes the Minneapolis–St. Paul Metropolitan Council’s requirements for municipal plans in the region (Metropolitan Council, 2015), Florida’s statutory mandate for planning consistency (The 2020 Florida Statute, 2020), and the modern Dutch planning system (Needham. 2005; Malecha et al., 2018). For the western Houston study area, the most planning and regulatory legitimacy rests with the municipal government, thus the City of Houston is best placed to assume this authority, identifying and reconciling instances of plan inconsistency.

Findings by Plan Type

Table 1 indicates that plans with an environmental emphasis (Gulf-Houston Regional Conservation Plan, Houston Parks & Recreation Department Master Plan, West Houston Trails Master Plan, and Energy Corridor Bicycle Master Plan) or a focus on hazard mitigation (Houston Stronger, Harris County Flood Control District Federal Briefing, City of Houston Hazard Mitigation Plan Update, and Addicks and Barker Reservoirs Master Plan) contained many policies aimed at reducing flood vulnerability (35 and 22, respectively). The overall policy scores also were very high for these plans on average (213.3 and 210.3, respectively). However, the policies in transportation plans (Houston-Galveston Regional Transportation Plan/Transportation Improvement Plan, Energy Corridor District Unified Transportation Plan, and West Houston Mobility Plan) increased vulnerability (14 of 17) more often than they reduced it (3 of 17), typically by guiding development toward hazard-prone locations. The overall policy score average per plan was negative (-28.0) for transportation plans. Results were mixed for comprehensive-style multipurpose plans (Our Great Region, Plan Houston, Energy Corridor District Master Plan, Energy Corridor Livable Centers Plan, Memorial City Management District Service & Improvement Plan, Westchase District Long Range Plan, and West Houston Plan 2050), reflecting the diversity of policies often contained in such documents – from increasing development intensity on the one hand, to preserving critical habitat or scenic areas on the other.

Findings by Hazard Zone

Table 1 also compares the total policy scores for the three hazard zones the PIRS analysis was applied to. It reveals that the strongest and the most positive policy attention was paid to the 100-year floodplain. The floodplain surrounding Buffalo Bayou, in particular, was the focus of significant attention aimed at reducing vulnerability (see Figure 2). The total policy score for the 100-year floodplain averaged 53.1/plan across the network of plans. The score was significantly lower for the 500-year floodplain (34.9/plan, on average), and lower still for the Hurricane Harvey maximum extent hazard zone (28.7/plan).

This suggests that the network of plans focused heavily on mitigating flooding in the FEMA SFHA, the flood-hazard zone that has been the most familiar, the most strongly regulated, and for which proactive planning has been best incentivized (for example, meeting national floodplain development standards enables subsidized flood insurance under FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program). At the time of Harvey’s impact, such institutional drivers were far weaker with respect to the 500-year floodplain, although this may now be changing. Strong federal attention on the SFHA also may have provided some cover to local plan makers, enabling greater land-use restrictions, and thus strengthening resilience, compared with the other hazard zones.

The lowest policy scores by plan – as well as many of the lowest policy scores by district-hazard zone (e.g., Districts 6, 16, 18, 24, 25, 31, 33, 35, and Energy Corridor (see Figure 2)) – were in the Hurricane Harvey maximum-extent hazard zone, reinforcing the notion that policy attention was contingent in large part on perceived hazard risk and on the institutionalization of hazard awareness. Policies that increased vulnerability were more likely to target such areas, given their location outside the FEMA-designated flood zones. However, as Hurricane Harvey and other recent flood events have shown and research has documented (Blessing et al., 2017), flooding does not always respect hazard zones.

Findings from Specific Case-Study – Energy Corridor Management District:

An in-depth discussion of Houston’s Energy Corridor Management District (see Figure 2) is presented to help illustrate the broader patterns described previously. The Energy Corridor is the most heavily planned part of the western Houston study area, with more than 100 policies across 14 plans likely to affect flood vulnerability in some part of the district. This abundance of flood-vulnerability-related policies enabled an in-depth investigation of some of the drivers behind the resilience scorecard results, including examples of how polices across the network of plans aligned, conflicted, and affected different parts of the community in different ways.

Established in 2001 by the Texas Legislature to “promote, develop, encourage, and maintain employment, commerce, economic development, and the public welfare” (Energy Corridor District, 2015, as cited in Malecha et al., 2021; State of Texas Local Government Code, 2005, as cited in Malecha et al., 2021), the Energy Corridor District has been the focus of significant planning and policy attention from the city, region, and state. Straddling Interstate 10 and Buffalo Bayou and bordering the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs (which double as regionally significant parks), the Energy Corridor is a leading employment center in Houston, with designs for continued growth as a high-amenity mixed-use destination (Energy Corridor District, 2015, as cited in Malecha et al., 2021).

Findings from the PIRS analysis generally reflected those observed for the wider study area: more policies affecting the Energy Corridor District were working to strengthen resilience (65) than to increase vulnerability (52); scores generally were better for plans at higher administrative scales and for those that focused on environmental or hazard issues; and more positive policy attention was given to the parts of the district in the 100-year floodplain (policy score: +44) than to those in the 500-year floodplain (+30) or Hurricane Harvey maximum flood extent hazard zone (+1). A closer examination of the policies behind these scores revealed patterns, including conflicts between plan documents, that often were relevant to the broader study area, and perhaps even to Houston and the wider region. They help tell the story of how the existing network of plans influenced flood vulnerability in this part of Houston at the time of Hurricane Harvey’s impact in August 2017.

A majority of policies affecting flood vulnerability in the Energy Corridor District aimed at increasing flood-resilience – from promoting conservation subdivision design, preserving wetlands and riparian zones, and developing an integrated regional storm defense system (Our Great Region 2040 and West Houston Plan 2050); to land acquisition and conservation easements (Gulf-Houston Regional Conservation Plan); to buyouts of flood-prone homes (Houston Stronger), regulatory measures that ensured safety in future development (City of Houston Hazard Mitigation Plan Update), and improvement of reservoir outlet structures (Harris County Flood Control District Federal Briefing). Extensions and enhancements of park and trail networks, especially along drainageways, also were suggested in multiple plans (Houston Parks & Recreation Department Master Plan, Energy Corridor District Bicycle Master Plan, and West Houston Trails Master Plan).

However, many policies directed at the same part of the city encouraged intensification of development near transit (Plan Houston), large-scale redevelopment and infill (Energy Corridor District Master Plan, Energy Corridor Livable Centers Plan, and Energy Corridor District Unified Transportation Plan), and new transportation corridors to induce development (West Houston Plan 2050 and West Houston Mobility Plan); some even suggested financial incentives to help accomplish these goals (Our Great Region 2040). Although appropriate in less hazardous places, such density- and development-focused policies increased vulnerability when being implemented in flood-hazard areas without sufficient attention to mitigation. They also conflicted with the direction of much other guidance (aimed at reducing flood vulnerability) and made no mention of this potential discord or how it should have been resolved, such as by asserting the primacy of hazard mitigation rules/actions in flood-hazard areas. Also notable was the distribution of these policy examples among plan scales and types: following broader trends seen throughout the study area, policies aimed at reducing vulnerability were found most often in plans at higher administrative scales and focusing on environmental or hazard issues, whereas policies increasing vulnerability were more frequently found in the local plans and those focused on transportation or development.

The Energy Corridor District also exemplifies the disparity in policy attention with respect to the three hazard zones. A higher policy score for the district’s 100-year floodplain (SFHA) was the result of many policies focused on protecting riparian and other flood-prone areas from development (City of Houston Hazard Mitigation Plan Update and Our Great Region 2040), as well as conserving or expanding existing parkland (West Houston Trails Master Plan and Houston Parks & Recreation Department Master Plan), much of which coincided with the SFHA. Fewer such policies applied in the 500-year floodplain, which also was the focus of policies aimed at increased development (Energy Corridor District Unified Transportation Plan and Energy Corridor District Master Plan). Policy conflict was even more apparent in the Hurricane Harvey maximum flood extent hazard zone; many parts of the district that flooded during the storm but were located outside the acknowledged floodplains were the focus of intense development pressure and related policies (Energy Corridor Livable Centers Plan and West Houston Mobility Plan). Results of the spatial plan evaluation therefore suggest that planning in the Energy Corridor District at the time of the impact of Hurricane Harvey was proceeding with some awareness of flood risk, but that was directed much more toward the established, regulatory SFHA.

This may go some way toward explaining the massive destruction that occurred in this otherwise relatively well-planned and prosperous part of the city. A much stronger focus on the known floodplain – almost as if it were the only hazard area worth worrying about, despite the recent trend toward larger-than-expected flood events – appeared to have exacerbated the consequences from Hurricane Harvey. In many ways, this is a stark example of the safe development paradox (Burby, 2006): focusing on large structural interventions to safeguard new development from disasters inadvertently increases the human and economic costs of disasters when those systems fail or are exceeded. In the Energy Corridor District, which is located immediately downstream from the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs, planners and decision makers appear to have recognized the need to restrict development in the most flood-prone area (100-year floodplain), but they also were guiding new and/or intensified development toward proximate parts of the city, many of which were at only slightly higher elevation. Thus, when Hurricane Harvey’s relentless rainfall necessitated the opening of the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs – to prevent additional flooding and their potential rupture and collapse – much of the community was inundated, leading to more catastrophic damage than would have occurred had the area not been deemed safe and thus intensely developed without adequate mitigation measures.

Plan conflict was also observed in the case of several regional plans with policies spatially focused on upstream areas, which nevertheless were likely to affect flood vulnerability along Buffalo Bayou and in the Energy Corridor District. The Gulf-Houston Regional Conservation Plan aimed to preserve upland Katy Prairie as part of a broader Prairie Conservation Initiative, likely reducing pressure on the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs and retaining or enhancing resilience along Buffalo Bayou. However, the West Houston Plan 2050 discussed the need for a new Prairie Parkway in the same area to accommodate future growth. Unless the development induced by such a major roadway addition proceeds extremely cautiously, the likely result will be reduced storage area for storm water, thereby increasing downstream vulnerability to flooding.

References

Malecha, M. L., Woodruff, S. C., & Berke, P. R. (2021). Planning to Exacerbate Flooding: Evaluating a Houston, Texas, Network of Plans in Place during Hurricane Harvey Using a Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard. Natural Hazards Review, 22(4), 04021030. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000470

Malecha, M. L., Brand, A. D., & Berke, P. R. (2018). Spatially Evaluating a Network of Plans and Flood Vulnerability Using a Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard: A Case Study in Feijenoord District, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Land Use Policy, 78, 147-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.06.029

Yu, S., Brand, A. D., & Berke, P. R. (2020). Making Room for the River: Applying a Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard to a Network of Plans in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Journal of American Planning Association, 86(4), 417-430. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1752776

Neuman, M. (2004). Planning Houston: A City without a Planning Culture. Planning Models and the Culture of Cities, Barcelona, Spain.

Blake, E. S., & Zelinsky, D. A. (2018). National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Harvey. www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL092017_Harvey.pdf

Harris County Flood Control District. (2018a). Hurricane Harvey: Impact and Response in Harris County. Retrieved from www.hcfcd.org/Portals/62/Harvey/harvey-impact-and-response-book-final-re.pdf

United States Army Corps of Engineers. (2009). 2009 Master Plan: Addicks and Barker Reservoirs, Buffalo Bayou and Tributaries, Fort Bend and Harris Counties, Texas. Galveston, TX: United States Army Corps of Engineers Retrieved from www.swg.usace.army.mil/Portals/26/docs/2009%20Addicks%20and%20Barker%20MP.pdf

Woodruff, S. C. (2018). Coordinating Plans for Climate Adaptation. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 42(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18810131

Brody, S. D., Highfield, W. E., & Kang, J. E. (2011). Rising Waters: The Causes and Consequences of Flooding in the United States. Cambridge University Press.

Council, M. (2015). Local Planning Handbook. https://metrocouncil.org/Handbook.aspx

The 2020 Florida Statute, (2020). http://www.leg.state.fl.us/Statutes/index.cfm?App_mode=Display_Statute&Search_String=&URL=0100-0199/0163/Sections/0163.3177.html

Needham, B. (2005). The New Dutch Spatial Planning Act: Continuity and Change in the Way in Which the Dutch Regulate the Practice of Spatial Planning. Planning Practice & Research, 20(3), 327-340. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697450600568662

Blessing, R., Sebastian, A., & Brody, S. D. (2017). Flood Risk Delineation in the United States: How Much Loss Are We Capturing? Natural Hazards Review, 18(3). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000242

Burby, R. J. (2006). Hurricane Katrina and the Paradoxes of Government Disaster Policy: Bringing about Wise Governmental Decisions for Hazardous Areas. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 604(1), 171-191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716205284676