Case Study Date: 2020

Nijmegen is a city inside the province of Gelderland. The Waal River flows through the city, making the city prone to riverine flooding. To protect Nijmegen from flooding while enhancing its spatial quality, the flagship project of the national Rome for the River project has been targeting the city.

Brief Summary of Findings

The network of plans in Nijmegen is generally integrated in enhancing flood resilience, with the policies concerning flood safety and natural protection making a particularly important contribution. However, policies at different administrative scales lack consistency in some places, with some socially vulnerable neighborhoods receiving comparatively little policy attention. The plan network oftentimes prioritizes development over flood resilience, though higher tier plans make up for these policy gaps.

Plans Evaluated

- Delta Plan: Room for the River Waal

- Provincial Environment Vision Plan

- Comprehensive Plan | Structure Vision

- Waterfront Master Plan

- Kanaalhavens Land Use Plan

- Centrum-Binnenstad Land Use Plan

- Verbreding Waalbrug Land Use Plan

- Mercuriuspark Redevelopment Plan

- Ooyse Schependom Land Use Plan

- Woenderskamp Land Use Plan

- Kern Lent-Visveld Land Use Plan

- De Stelt Land Use Plan

- Hof van Holland Land Use Plan

- Woonpark Oosterhout Land Use Plan

Nijmegen, the Netherlands

Nijmegen is a city along the Waal River. It is the location of the largest and the flagship project of the national Room for the River program. The city is inside the Dutch province of Gelderland and has a 2011 population of 164,223. Nijmegen’s Room for the River plan received the Excellence on the Waterfront Honor Award 2011 from the Washington, DC–based Waterfront Center for successfully combining flood safety with constructing a riverside park and with the close local community involvement. The twin goals of the Room for the Waal program are to protect the city of Nijmegen from future floods and to enhance spatial quality. At Nijmegen, river dikes were not simply raised or strengthened: Instead, the northern river dike was relocated to create a wider floodplain that gives future floodwaters more room to flow, reducing the threat to the city. In addition, all engineering projects were designed to do more than flood control; parks and nature areas were included in the designs as co-benefits of the initial flood safety goal.

Findings of the Overall Network of Plans:

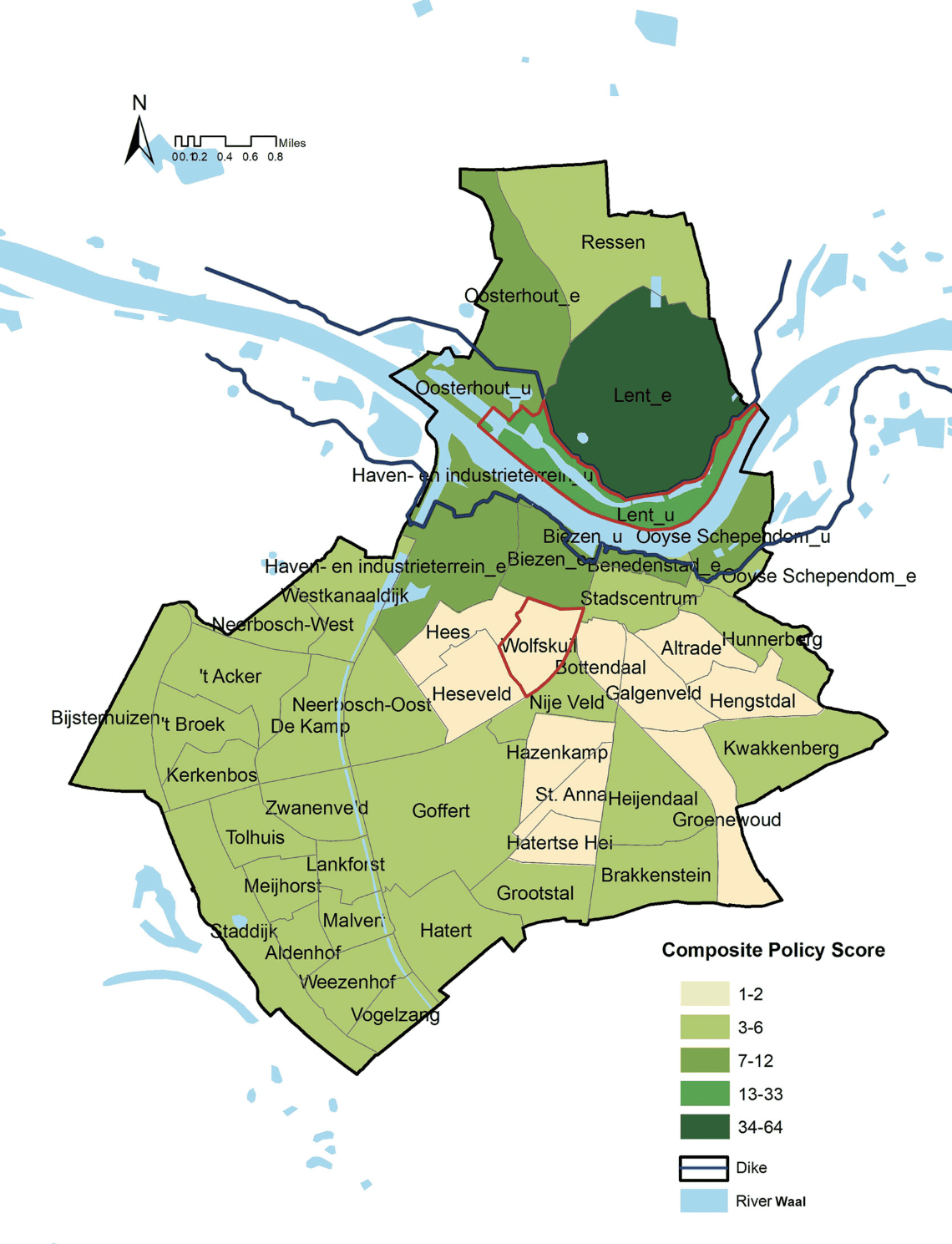

The overall policy scores indicate that the network of plans generally supports vulnerability reduction in the 44 neighborhoods in Nijmegen. Composite policy scores for neighborhoods derived from the 14 plans collected at the national, provincial, and local levels are all positive, ranging from +1 (Bottendaal, Galgenveld, Altrade, Hengstdal, St. Anna, Hatertse Hei, Heseveld, Wolfskuil, and Hazenkamp neighborhoods) to +64 (the embanked portion of the Lent neighborhood; see Figure 1). Compared with findings in six U.S. cities (Berke et al., 2019), plan integration and vulnerability reduction are generally stronger and more consistent in Nijmegen, suggesting a difference in flood mitigation priorities between the two countries. The Dutch planning system appears to follow a trend of increased streamlining and coordinating of policies into spatial plans, which perhaps reflects the long-standing system of consultative planning there (Faludi & van der Valk, 2013). However, there is high variability in overall mean policy scores between the embanked and unembanked neighborhoods; the overall mean policy score is 5.18 for embanked neighborhoods and 13.00 for unembanked neighborhoods. This suggests different policy emphases of the network of plan documents in targeting different spatial areas in Nijmegen, with unembanked neighborhoods receiving more attention in reducing risk, on average, than their embanked counterparts. Scores are also somewhat more consistent in the unembanked neighborhoods, with a standard deviation of 5.61 compared with 9.26 in embanked neighborhoods. These broad trends can be better understood by closely inspecting the individual plan scores.

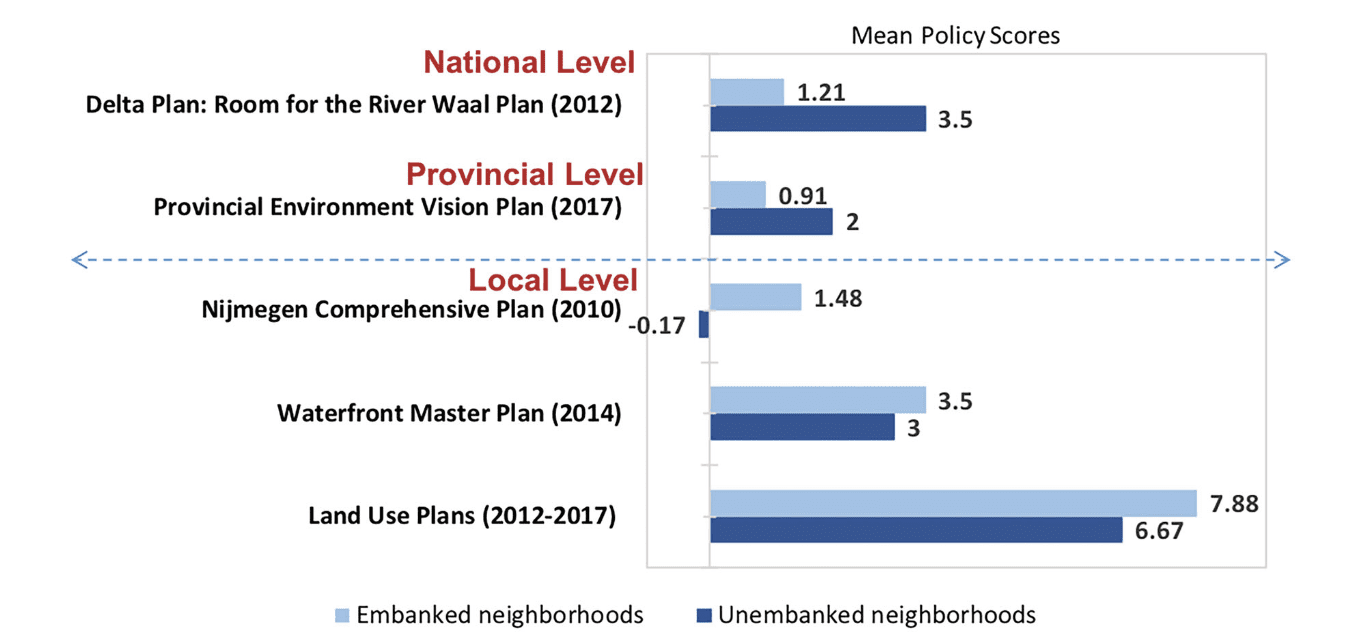

Policy scores for different administrative scales reveal considerable differences between unembanked and embanked neighborhoods (see Figure 2). At the national scale, the Delta Plan: Room for the River Waal reflects a primary goal of flood safety with a particular focus on unembanked riverine areas. The mean policy score for the enlarged unembanked neighborhoods that are at greater risk to riverine flooding is 3.50, compared with a mean policy score of 1.21 for embanked neighborhoods that are at lower risk to riverine flooding. This plan accommodates relocating the dike in response to the decision taken by the Dutch national parliament following the 1993 and 1995 near-flood events to make more room for the river. With regard to riverine flood resilience, Nijmegen’s plan-study, associated with the Delta Plan, aspires to a high-water reduction of 34 cm (more than the national mandatory standard of 27 cm), anticipating future increases in River Waal discharges until 2050. The plan’s core strategy is to widen the riverbed by moving the dikes inland, resulting in enlarged unembanked areas.

At the provincial level, the Environment Vision Plan sets up a comprehensive framework to accomplish the twin goals of the Room for the River program: to protect the city of Nijmegen from flooding and to preserve the ecological values in the natural network. Results show that more policy attention is paid to the unembanked neighborhoods (mean policy score = 2.00) than to the embanked neighborhoods (mean policy score = 0.91). The natural networks in the enlarged unembanked areas are particularly important because the ecological values in this area offer significant riverine flood reduction benefits, as well as other recreational and wildlife habitat protection benefits.

At the local scale, Nijmegen adopted three types of municipal plans, with each giving more attention to flood resilience in embanked neighborhoods compared with unembanked neighborhoods. The Nijmegen Comprehensive Plan moderately supports reducing risk across the embanked neighborhoods (mean policy score = 1.48). However, policies focused on the unembanked neighborhoods place more emphasis on promoting economic development (mean policy score = -0.17), despite the fact that unembanked areas are more likely to experience flooding. Nijmegen’s Waterfront Master Plan targets the neighborhoods of Biezen and Haven-en industrieterrein, both of which contain embanked and unembanked portions; again, greater attention is given to the embanked areas (mean policy score = 3.50) than to the unembanked areas (mean policy score = 3.00). For the ten local land use plans, results indicate that they generally support flood risk mitigation. Consistent with the other municipal plans, greater attention is paid to embanked neighborhoods (mean policy score = 7.88) than to unembanked neighborhoods (mean policy score = 6.67). In the Netherlands, most land use planning occurs at the local level; thus, local plans are especially detailed and focused, resulting in a higher number of total policies (and higher mean scores) than plans at the national and provincial levels.

In summary, the PIRS findings reveal patterns – and sometimes inconsistencies – in Nijmegen’s network of plans, which affect flood resilience in relation to the Room for the River program. The overall plan score is positive, indicating an integrated approach to flood safety, but significant differences exist in the results for embanked and unembanked neighborhoods. National and provincial-level plans generally give greater attention to unembanked neighborhoods by protecting natural riparian networks and focusing on safeguarding flood resilience in the enlarged unembanked neighborhoods, resulting from the Room for the River Program. Municipal plans place greater emphasis on embanked neighborhoods, focusing on building flood resilience to accompany development. Thus, higher tier plans are making up for policy gaps in local plans.

Note. Adapted from Making Room for the River: Applying a Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard to a Network of Plans in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, by S. Yu, A. D. Brand, P. R. Berke, Journal of American Planning Association, 86(4), p.424 (https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1752776). Copyright 2020 by American Planning Association, Chicago, IL.

Note. Adapted from Making Room for the River: Applying a Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard to a Network of Plans in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, by S. Yu, A. D. Brand, P. R. Berke, Journal of American Planning Association, 86(4), p.425 (https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1752776). Copyright 2020 by American Planning Association, Chicago, IL.

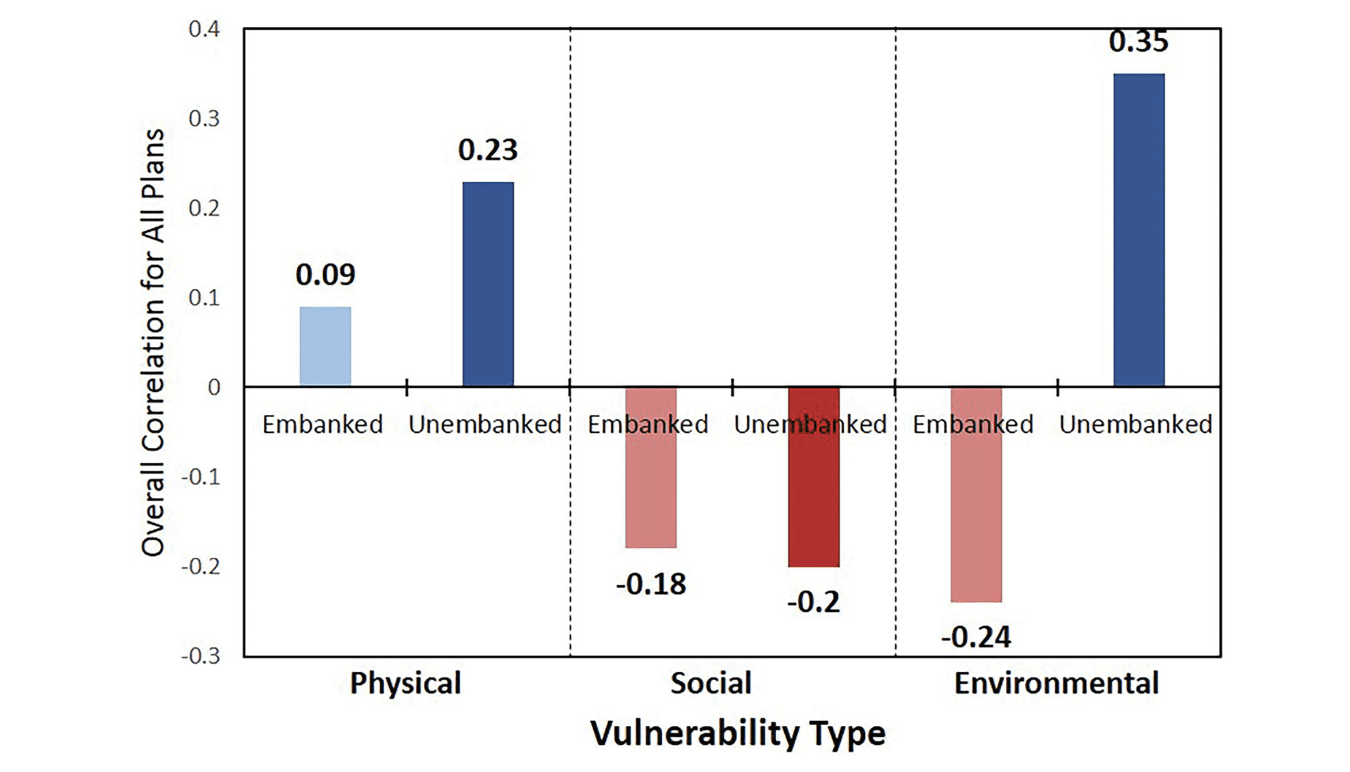

Figure 3 shows the correlations between the summed policy scores of all plans and the level of three types of vulnerability (physical, social, and environmental) at the neighborhood scale for embanked and unembanked areas. It reveals that the higher the physical vulnerability in a neighborhood, the higher the policy scores, thus indicating that the network of plans prioritizes vulnerability reduction in areas with greater physical vulnerability. Unembanked neighborhoods have the highest positive correlation (0.23), and embanked neighborhoods have a small positive correlation (0.09). The positive correlations between policy scores and physical vulnerability for embanked and unembanked neighborhoods indicate that the plan network prioritizes vulnerability reduction in neighborhoods with comparatively high vulnerability. This finding suggests that Nijmegen’s network of plans aligns with the flood safety goal of the Room for the River Waal program for reducing physical vulnerability, especially for existing development in unembanked neighborhoods.

Note. Adapted from Making Room for the River: Applying a Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard to a Network of Plans in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, by S. Yu, A. D. Brand, P. R. Berke, Journal of American Planning Association, 86(4), p.426 (https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1752776). Copyright 2020 by American Planning Association, Chicago, IL.

In contrast, the overall correlation among the three tiers of plans indicates an inverse relationship between policy scores and social vulnerability in both embanked (-0.18) and unembanked (-0.20) neighborhoods. This suggests that vulnerability reduction is not prioritized in highly socially vulnerable neighborhoods. This resembles findings in the United States (Berke et al., 2019), where PIRS analyses reveal a structural pattern of less policy attention in neighborhoods that have greater social vulnerability. The inverse relationship raises a hazards-related social justice issue: Less effort to reduce vulnerability corresponds with escalating hazard losses in more socially vulnerable neighborhoods.

For environmental vulnerability, the correlation results are negative for the embanked (-0.24) neighborhoods and positive for the unembanked (0.35) neighborhoods. This finding indicates that the Nijmegen network of plans gives more support to protecting environmentally sensitive areas in the unembanked neighborhoods but does not prioritize protecting environmentally sensitive areas in the embanked neighborhoods. The negative relationship is likely due to fewer environmentally sensitive areas and open space in embanked neighborhoods, which leads to less demand for preservation and other forms of positive policy attention. Thus, according to the scorecard analysis, the Nijmegen network of plans successfully pursues nature preservation – associated with the Room for the River Waal program’s second goal, spatial quality – in the enlarged unembanked neighborhoods but misses an opportunity to similarly prioritize flood vulnerability reduction with respect to the environment throughout the city.

Findings from Specific Case-Study – Wolfskuil and Lent Neighborhoods:

The case study of Wolfskuill and Lent Neighborhoods offers a clearer picture of how plans work with or against one another and how they correspond with varying levels of the three types of vulnerability in two different neighborhoods, representative of the general pattern of correlations discussed in the previous section. Wolfskuil is an embanked neighborhood with relatively low physical vulnerability (€171,000 compared with the mean of €220,000 in Nijmegen), high social vulnerability (index score = 6), and no environmental vulnerability (0.0% of geographic area designated as protected area), with a comparatively low policy score (+1). In contrast, the unembanked area within Lent has moderately high physical vulnerability (€249,000), low social vulnerability (1), and high environmental vulnerability (59.3%), with a very high policy score (+18).

Wolfskuil exemplifies how the city gives limited policy attention to reducing vulnerability in a neighborhood that is higher than average in social vulnerability (e.g., low income with a high percentage of immigrants), does not contain environmentally sensitive areas, and has lower than average physical vulnerability. The composite plan score is the lowest among the city’s 44 neighborhoods. The national Delta Plan is the only plan that focuses on Wolfskuil and only includes a single policy that applies to all embanked neighborhoods, indicating that the high-water level will be reduced by 27 cm due to relocating the dike (350 m away from the River Waal) and digging a wider channel. Provincial and local plans do not include policies aimed at reducing stormwater runoff in the neighborhood. In the case of local plans, this finding is unexpected. Unlike unembanked areas where precipitation drains to the river directly, stormwater drainage and retention facilities are needed in embanked neighborhoods that do not naturally drain to the river (Malecha et al., 2018). The dearth of applicable policies may be due to the conservative nature of the land use plans for the Wolfskuil neighborhood, which focus on regulating the status quo rather than pursuing new development. But it could be due to the fact that the plans ignored the uneven impacts of hazards on socially vulnerable populations.

In contrast, Lent exemplifies how the city’s network of plans give strong policy attention to reducing vulnerability in unembanked neighborhoods with low physical vulnerability, a high percentage of environmentally sensitive areas, and low social vulnerability. Local comprehensive and land use plans include policies that support an ambitious push for new development in the enlarged unembanked lands. Examples of pro-development policies include zoning requirements that allow several large residential projects (e.g., Waalfront with 2,600 units, and The Selt with 400 units) and water-focused businesses, as well as a public investment for a 24-hour home care facility for the elderly. However, as indicated by the high overall policy score for all plans, more attention is placed on the location of future development and designing structures that can accommodate and adapt to flooding. For example, the Delta Plan and the Provincial Environmental Vision Plan consistently place a high degree of support on preventing increased vulnerability. Examples of prominent policy themes in these plans include the following:

- acquisition funding for relocating existing residential developments that are more vulnerable to flooding due to widening of the river,

- developing an ecosystem enhancement program for the new sand island that provides flood protection and neighborhood amenity values, and

- infrastructure investments for bridges across the River Waal that have flexible designs and adapt to rising water levels to ensure safe crossing during a flood event.

References

Malecha, M. L., Brand, A. D., & Berke, P. R. (2018). Spatially Evaluating a Network of Plans and Flood Vulnerability Using a Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard: A Case Study in Feijenoord District, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Land Use Policy, 78, 147-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.06.029

Yu, S., Brand, A. D., & Berke, P. R. (2020). Making Room for the River: Applying a Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard to a Network of Plans in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Journal of American Planning Association, 86(4), 417-430. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1752776

Faludi, A., & van der Valk, A. J. (2013). Rule and Order Dutch Planning Doctrine in the Twentieth Century (Vol. 28). Springer Science & Business Media. Berke, P. R., Malecha, M. L., Yu, S., Lee, J., & Masterson, J. H. (2019a). Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard: Evaluating Networks of Plans in Six US Coastal Cities. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 62(5), 901-920. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2018.1453354