Case Study Date: 2020; 2021

Nashua is a mid-size city in New England. It is prone to riverine flooding due to its location at the confluence of the Merrimack and Nashua rivers.

Brief Summary of Findings

The network of plans in Nashua reduces vulnerability to flooding in every district hazard zones in the city. Still, inconsistencies exist between plans. For instance, the hazard mitigation plan fails to target the vulnerability hotspots. Meanwhile, the plans dealing with transportation, economic development, and flooding focus on post-disaster emergency response after a disaster, thus under-exploiting the functions of other policy tools.

Plans Evaluated

- Nashua Master Plan

- Consolidated Plan for CBDG and HOME

- Nashua Downtown Riverfront Development Plan

- Beyond the Crossroads Positioning Nashua to Compete in the Global Economy

- City of Nashua Hazard Mitigation Plan

- Energy Plan for the City of Nashua

- Exit 36 Study Area and Future Conditions

- Nashua Economic Development Plan

- Nashua Sanctuary Stewardship Plan

- Nashua Tree Streets Neighborhood Analysis and Overview

- Nashua Transit System Comprehensive Plan (2012-2025)

- Complete Streets in Nashua

- Nashua Downtown Master Plan

- East Hollis Street Area Plan

Nashua, NH

Nashua is a mid-size New England city with about 90,000 residents. Due to its location at the confluence of the Merrimack and Nashua rivers, the city is susceptible to riverine flooding. Nashua is committed to building community resilience, as indicated by several pioneering initiatives it is participating. For instance, Nashua signed on to the Mayors National Climate Action Agenda in 2017. The city is incorporating resilience and climate adaptation into multiple planning initiatives, including the Downtown Riverfront Development Plan, the Climate and Health Adaptation Plan, and the Hazard Mitigation Plan. It is partnering with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in its first attempt to develop a citywide resilience plan (NIST, 2016).

Nashua recognizes that more must be done to coordinate its increasingly diverse resilience initiatives (Kates, 2019). Concerns raised by city staff and leaders from outside of government focus on the inconsistent prioritization of climate change adaptation and hazard mitigation across city departments, variable stakeholder engagement, and weak coordination between urban planning and emergency management (City of Nashua, 2018). As mentioned, the city’s Office of Emergency Management (OEM) took up this challenge by leading the development of a successful grant from the National League of Cities in 2018 to support the application of PIRS (National League of Cities, 2018, as cited in Berke et al., 2021).

Findings of the Overall Network of Plans:

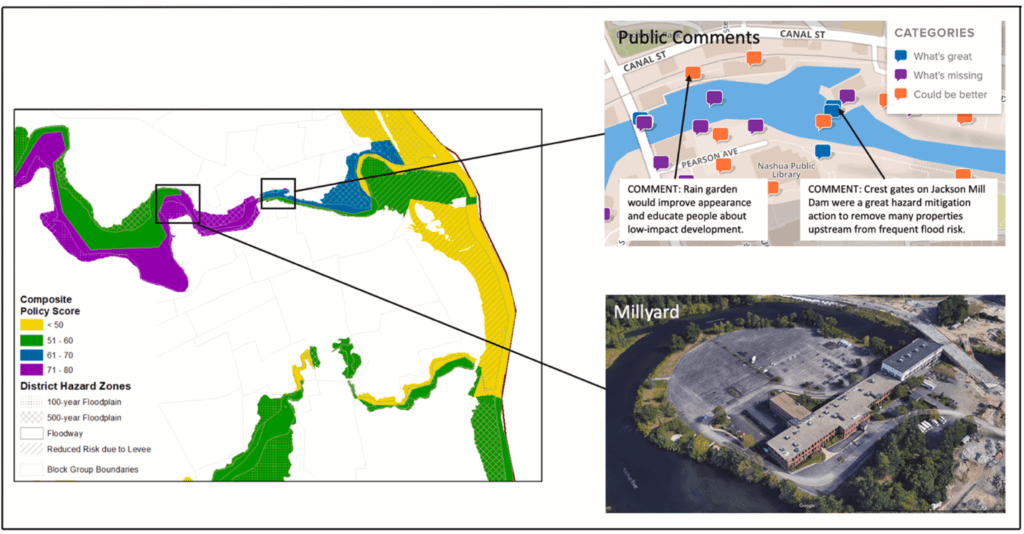

The composite index score generated from the PIRS evaluation indicates that all district hazard zones in Nashua receive positive scores, indicating that plan policies support vulnerability reduction in all the zones (see Figure 1). Several prominent policy themes in multiple plans (master plan, riverfront development plan, hazard mitigation plan) work together to prevent new floodplain development along riverfront districts from heightening the vulnerability there, including, for example:

- land use regulations for new development aimed at reducing the vulnerability of undeveloped floodplain riparian lands (e.g., stream buffer setbacks and subdivision standards that require clustering and dedication of open spaces);

- land acquisition in high priority conservation areas in undeveloped floodplains;

- green infrastructure investments for stormwater management facilities like rain gardens and flood detention ponds; and

- development limits tied to evacuation times for new development in undeveloped floodplains.

Note. Adapted from Using a Resilience Scorecard to Improve Local Planning for Vulnerability to Hazards and Climate Change: An Application in Two Cities, by P. R. Berke, J. Kates, M. L. Malecha, J. H. Masterson, P. Shea, S. Yu, 2021, Cities, 119, p.8 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103408). Copyright 2021 by Elsevier Ltd.

While Nashua’s effort is strong, weaknesses and inconsistencies exist among plans. In some instances, plans are in conflict. For example, the riverfront development plan includes specific policies to limit density at the flood-prone parts of the historic Millyard site along the Nashua River (see Figure 1). However, at the same time, the Nashua Economic Development Plan includes policies that propose increased density to support development of a technology park at the same site. Another example is a policy in the hazard mitigation plan that specifies flood mitigation improvements of specific roads that frequently flood and cut-off neighborhoods from essential facilities (grocery stores, pharmacies, schools). However, the same issue has been neglected by the transportation plan.

Notably, Nashua’s hazard mitigation plan has multiple shortcomings. Policies in this plan do not target the vulnerability hotspots deemed of high priority for protection by the crowdsourcing mapping data, such as poor neighborhoods and historic districts exposed to flooding. Policies also fail to prioritize addressing the spatial land use issues related to limiting or avoiding floodplain development.

Finally, several plans dealing with transportation, economic development, and flooding take a narrow focus on post-disaster emergency response. Examples of such policies include the prevention of traffic signal failure to enhance mobility of emergency responders after a disaster. Also included is the installation of electrical generators in the city emergency operations center. Yet, considerably less attention has been given to the more proactive approaches that support building resilience before a disaster.

“In contrast to a previous planning process, which was really aimless and undisciplined, the Scorecard process produced a more coordinated, spatially specific network of plans for the city. It gathered information to help us with the Nashua 2019 Hazard Mitigation Plan. Seven policies were revised to reduce vulnerability in the city’s districts [that] scored high in physical and social vulnerability.

“The City plans to use the Scorecard results in its upcoming Master Plan development as well as [in] an application for the LEED for Cities certification. So, working with the Coastal Resilience Center researchers, Nashua brought in around 40 local leaders to learn about the process and serve as ‘ambassadors of resilience’ for the community.

“Emergency Managers really need to connect with their community planners. I know that during the five-year update of each Hazard Mitigation Plan across jurisdictions around the country, it’s typically one of the major involvement points for community planners… the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard process really helped us to understand the importance of that relationship. I think it’ll be an opportunity for Emergency Managers to better understand ways that they can reduce risk in their communities, rather than just responding and recovering.”

Justin Kates, CEM

Director of Emergency Management

City of Nashua, NH

References

Berke, P. R., Kates, J., Malecha, M. L., Masterson, J. H., Shea, P., & Yu, S. (2021). Using a Resilience Scorecard to Improve Local Planning for Vulnerability to Hazards and Climate Change: An Application in Two Cities. Cities, 119, 103408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103408

Berke, P. R., Masterson, J. H., Malecha, M. L., & Yu, S. (2020). Applying a Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard to Practice: Experiences of Nashua, NH, Norfolk, VA, Rockport, TX [Preliminary report]. https://planintegration.com/cross-case-paper

National Institute of Standards and Technology. (2016). Community Resilience Planning Guide for Buidlings and Infrastructure Systems. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.1190v1

Kates, J. (2019). Toward a Resilient Nashua, New Hampshire. https://www.nist.gov/blogs/taking-measure/toward-resilient-nashua-new-hampshire

City of Nashua. (2018). Resilience Dialogues: Synthesis Report: Nashua, New Hampshire. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1tGs_U7s2d9jVi2mYja0mcvsrgrtww9us/view